A Pit Stop with Pedro Parra in Chile

- Joanna Simon

- May 13, 2020

- 14 min read

Updated: Sep 16, 2020

The genie in the pit: Pedro Parra in one of thousands of soil pits (calicatas) he has dug, but this one is special: it's amid vines in Itata that produce his own wines

“Chile is a great terroir used in a very boring way.” You always know where you are with Pedro Parra, soil scientist extraordinaire. They weren’t quite his opening words when I met up with him in Chile for the first time in a while, but they weren’t far off. He had already summarily dismissed Carmenère and a few other grape varieties.

More of that in a moment, but to give the context, I had just arrived in Chile and was in Itata for the first time. On previous trips – a while ago – I’d been further south to Bío Bío and up to Elqui Valley in the north and taken in a lot of regions in between, but not Itata. In fact, it’s not so surprising. Although Itata was one of the first places in Chile to be settled by the 16th-century Spanish Conquistadores, by the end of the 20th century it had become largely forgotten: a poor, rural, largely forested region, its undulating, granite hills punctuated by small holdings and gnarled, rather neglected, old bush vines, the fruit of which was sold, if at all, for a pittance. It is in the current century, and essentially within the past 10 years, that Itata has been rediscovered, one example of the significant changes to the Chilean wine scene in recent years. To see how much things have moved on it’s worth looking up a few key words in Peter Richard’s The Wines of Chile, a seminal book when published in 2006 (and still a highly readable one). País, Chile’s second most planted wine grape variety, then as now, barely gets a mention. When it does it’s anything but favourable. It heads the list of four “irredeemably mediocre vines that are [Chile’s] historic legacy”. There are references to “grubbing up”, to the variety serving “little purpose other than making the most basic of wine” and the need for a thorough plan for the Itata region to phase out and replace non noble varieties with noble varieties, or pine trees. Itata itself doesn’t merit a dedicated chapter and only two Itata wineries are profiled. Cinsault, of which Chile has more than 600 hectares, mostly in Itata, is mentioned only in the context of it being grafted over to Sauvignon Blanc at the Canata winery in Bío Bío. But, then, Chile isn’t mentioned in the Cinsault section of the definitive Wine Grapes by Jancis Robinson, Julia Harding and José Vouillamoz, published in 2012.

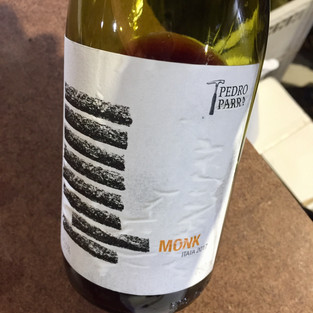

Itata and its old vines: the Cinsault (centre) is used for Pedro Parra's single-vineyard wine 'Monk' (scroll down for tasting notes); the País could be 150 years old

It’s no exaggeration to say that País and Cinsault, together with Carignan, are exciting wine grapes in Chile today. They’re not going to displace the international super-stars – Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Chardonnay et al – or even Carmenère, but Chile’s País, Cinsault and Carignan vines are old and that’s the key to their potential. That and the soils – not least the granitic soils. Which brings me to another near absentee from the pages of The Wines of Chile: the man who has variously been described as “the leading figure of the ‘New Chile’ movement”, “one of the most influential terroir specialists in the world” and a “modern-day Indiana Jones”. Yes, Pedro Parra, the soil and vineyard mapping expert credited with finding and realising the potential of many of Chile’s top vineyard sites and moving the vineyard focus of leading wineries, such as Montes, out of the fertile plains and up into the hills, moves which have transformed both quality and style.

"He is said to have been responsible for the digging of over 22,000 soil pits"

One of things for which Parra is famed is calicatas – pits dug in the vineyards to examine soils, geology and vine roots. Indeed, he’s very often to be found in one – hardly surprising when you know that he’s said to be responsible for the digging of more than 22,000. You can barely visit a producer today without being encouraged to step down into at least one soil pit (no hardship: they’re always instructive, unlike bottling lines, the curse of any wine trip). They’ve had a huge impact on what is planted where in Chile in the last dozen-plus years, but they didn’t get much of a look-in in the 2006 The Wines of Chile.

That Parra consults for vineyards in Burgundy (where he worked for 12 years), Oregon, Okanagan, Sonoma, Argentina, Armenia, South Australia, Italy, Spain, Champagne and Uruguay says all you need to know about the regard in which he’s held worldwide. And he’s hands-on. He doesn’t have a team, although since last year he has been assisted by Paul Krug in projects in Burgundy, Champagne and South Australia. And yes, that is Krug as in Champagne, seventh generation and son of Olivier. Paul Krug’s background couldn’t be more different from Pedro Parra’s non-wine upbringing in the city of Concepción in Bío Bío, except that Krug is a graduate of the Institut National Agronomique de Paris-Grignon, where Parra did his PhD on terroir, following a Masters in Precision Agriculture (which in turn followed forestry management and playing jazz saxophone in cafés and bars – "I'm a terrible player"). In case you’re wondering, the two met when Krug was working at an Oregon estate for which Pedro was consulting. If Parra is beginning to sound like a continent-flitting consultant, who, until this year’s forced grounding, was always in someone else’s vineyard or on a flight in between, it’s not the case (although I suppose his wife and three children might disagree). He has been a partner in wine projects since 2003, collaborating with winemaker François Massoc (a Concepción man like himself) and Michel Liger-Belair (Vosne-Romanée) in Aristos, and with Massoc, winemaker Paco Leyton and businessman Albert Cussen in Clos des Fous since 2008.

Paco Leyton, winemaker of Clos des Fous, and the wines lined up for the tasting held at Pedro Parra's winery in Itata (scroll down for tasting notes)

The idea behind Clos des Fous was to make wines in a Burgundian way – small volumes and non-interventionist – from extreme terroirs, mostly dry-farmed, and using limited oak; “honest, drinkable wines” in Parra’s words. It was pretty revolutionary in Chile at the time. The original plan was white wines and Pinot Noir, but by last year it had grown to 14 wines. “Too many,” he says, before I can ask, adding that the hardest thing with four partners is to all agree. Candid as ever: “the problem is we don’t have the same palate.” The vineyards they've used stretch from north to south and east into the Andean ranges – from Limarí’s limestone to Itata’s granite to the volcanic tufa and basalt of the Malleco region even further south. “We didn’t think about logistics,” he admits. In 2013, he fulfilled a dream to produce his own wines in his native Itata, creating Pedro Parra y Familia, focusing on dry-grown, old-vine Cinsault and País. He’s also a partner in Altos Las Hormigas over the Andes in Mendoza, with Italian friends Alberto Antonini, Antonio Morescalchi and Attilio Pagli and winemaker Leo Erazo-Lynch. And there’s Causse du Théron in Malbec’s French heartland, Cahors, with the same four. The wines are made by Leo Erazo, with local vigneron Sébastien Sigaud, using grapes from a steep (I can vouch for how steep it is), two-hectare kimmeridgian limestone slope within the Sigaud family’s Metairie Grande du Théron estate.

"You learn a lot about a producer from the wines they serve you at dinner"

Going back a bit, I'd encountered Pedro Parra in and around a soil pit or two in Chile, but it was at a small tasting and lunch in June 2012, organised by Liberty Wines in London (which now imports his wines as well as Clos des Fous, Altos Las Hormigas and Causse du Théron), that I really began to understand the ground-breaking (sorry, no pun intended) significance of what he was doing. He gave a gripping presentation on terroir, rock and soil types, unlike anything I’d heard before. Last year I had the opportunity to catch up with him again, and with more time. Itata was the place to do it (although I wouldn’t have said no to his home “by a very beautiful lake and volcano” three hours south in Bío-Bío). We had dinner – a lakeside tapas and barbecue at the home of a very accomplished chef friend of his in Concepción – then headed out to Itata the next day. You learn a lot about a producer from the wines they serve you over lunch or dinner (just as you can tell how they rate you by the wines they line up for you to taste). I’m always encouraged by one who has the imagination, open mindedness and confidence to serve other producers’ and regions’ wines. You’d be surprised at the Champagne houses that still serve nothing but their own Champagnes throughout a long, multi-course meal. For dinner, Parra chose some Clos des Fous wines, including the debut 2010 Chardonnay (orange in colour, a sherryish note on the nose, oily texture, but convincingly lively and mineral on the palate) and 2012 Clos des Fous Grillos Cantores Cabernet Sauvignon from Alto Cachapoal (violet and herb nose, gravelly mineral freshness and silky texture). But he also served Domaine Guiberteau Saumur Blanc 2015 and Domaine Lafarge-Vial Fleurie La Joie du Palais 2016 – the Saumur from tuffeau (local Loire limestone), the Fleurie from granite. The next day we headed to the the Itata vineyards and his winery. Pedro did most of the talking. He has a lot to say (on vines, grape varieties, soils, rocks, his beloved Itata), which you can take as a promise or a warning.

"I hate Carmenère, it has no character"

Let’s start with grape varieties. Chile may not make the most of its terroir in Parra’s view, but, he says, it has great diversity of terroirs; what it doesn’t have is diversity of grape varieties. And with that he lays into Carmenère, a variety that Chile has far more of than any other country. Could it be a signature variety? “I hate Carmenère, it has no character. Argentina was growing fast with Malbec and in Chile we thought we had to find something similar. Today, the big companies still want to produce it, but not the medium and small companies.” (For the record, I like Carmenère when it has some green freshness, briary fruit, soy-sauce smokiness and isn’t smothered in oak, but this is Parra’s moment, not mine.) What about Cabernet Sauvignon? “It’s difficult to produce fresher, more drinkable wines with Cabernet Sauvignon [in Chile]. It lacks complexity. You need to blend it. In Chile, the best Cabernets comes from sands and gravels and they’re all blends.” OK, what of Pinot Noir? “80–90 percent of the Pinot Noir in Chile is terrible clonal material. We need to try better Pinot Noir.” Later, he says he thinks that 50 percent of the Pinot Noir in Chile could be Meunier and that to judge Chile’s potential for Pinot you need to look at the plantings of the last seven or eight years. I asked about Syrah next. He mentioned the need for the right terroirs. And then he moved on to the varieties he favours: Cinsault, País, Grenache and Carignan.

"País has been less taken up than Cinsault. It's less sexy"

"Cinsault isn’t easy. It needs attention. It’s a little bit sweet. So, for me, you to have to use a percentage of whole bunch – 30, 40, even 50 percent” (the higher figures when there’s more quartz, the lower end when there’s less quartz). “The big companies have it now, as a marketing symbol, but not much of it.

“País has been less taken up. It’s less sexy. It’ll never produce great wine: it’s very productive; it can easily do 20 kilos a vine, so you have to find very, very poor soil. But I’d like to see more of it, especially for the UK.” The País he uses in one of his own Itata wines comes from Ñipas and could be 150 years old; no one knows. The Cinsault comes from the sub-region of Garilihue and is around 60 years old. In so far as these old vineyards are worked at all, it has to be by horse. It's still early days for Grenache in Chile. “No one is doing Grenache, but Chile has granite, and granite and Grenache are terrific. People are planting it now, but we don’t have old vines.” Although there's not much Grenache, there is going to be a little more soon. Parra is in the process of buying a vineyard, his first, in Ñipas – "a great location, view and old País". And with the opportunity to plant Grenache? "I will for sure!" Carignan is in a different position. It was the first variety that “the more risky people” started to revive in the early years of this century. Bush vines planted long ago by small farmers in the more remote parts of Maule survived and began to be rediscovered and nurtured by big and small producers. Another variety no one is doing is Gamay. And yet there’s granite in Chile, especially in Itata, and everything is gobelet in Itata, so, why no Gamay, Pedro? “Because we’re stupid.”

The undulating vineyards and slopes of Itata that remind Pedro Parra of Barolo (note the trademark geological hammer poking out of his pocket)

For all his opinions on grape varieties, they’re not his real focus. He says himself, “I care less about the grapes and more about soil.” And the soils he’s interested in are granite, limestone and volcanic tufa, especially when it’s volcanic with fractures in it, like basalt. There is, he says, limestone still to be discovered in Chile. “We need to find more in the middle and south, because the limestone in Limarí is good but it’s more about salinity than limestone.” And then he adds, almost as an afterthought: “After looking for limestone for so many years, I am now very happy with granite.” Which is what he has, of course, in Itata, reminding him of Galicia and Morgon/Fleurie, just as the undulating topography reminds him of Barolo. Analysis shows Itata’s granitic and schist soils to be typically low fertile, but Parra says that, on the contrary, these brown, decomposed granites are very fertile, not because they’re intrinsically so but because they’re very deep and very old, which is ideal for the long roots of old, dry-farmed, bush vines.

New and old rubbing shoulders in Pedro Parra's Itata winery

Pedro’s winery in Ñipas, tucked away amid the forests, vineyards and brown soils of Itata, is a trendily ramshackle old barn filled with an assortment of concrete cubes, stainless steel tanks, plastic egg fermenters, oak vats and barrels, demijohns, the occasional bit of ancient vineyard equipment and the sound of jazz coming from speakers. Winemaking is simple and hands-off with some whole clusters, natural yeast fermentations starting after six or seven days, eight to nine days fermentation at about 24º (26º maximum), ten days post-ferment maceration, then into either concrete or oak; smaller vessels, whatever the material, for better quality wines.

The wines are fresh, juicy, silky in texture, spicy/peppery and mineral. They have the hallmark mineral freshness of granite, they taste of the place, which is what Pedro is aiming at. Result. And he's just told me that there's more to come. Two new Cinsault wines – "what I consider to be my Gran Cru" – to be released when the virus situation allows. If that isn't something to look forward to, I don't know what is.

TASTING

Most of these wines were tasted a while ago, so I'm keeping the flavour notes brief while aiming to convey a feel for the wine and its style.

Pedro Parra Imaginador Itata Valley Cinsault 2017

From vines well over 50 years old in rocky quartzic granite soils in the Guarilihue sub-region. 30% whole bunch. Natural yeasts. 12 months' ageing in a combination of untoasted oak tanks, foudre and concrete vats. 14%

Bright, sweet, raspberry and cherry fruit with mineral, smoky white pepper notes. Silky and mineral-fresh.

Pedro Parra Pencopolitano Itata Valley Cinsault/País 2017

67% Cinsault, 33% País from old vineyards in Guarilihue and Portezuelo on very rocky quartzite granite. 30% whole bunch. Natural yeasts. 12 months' ageing in a combination of untoasted oak tanks, foudre and concrete vats. 14%

Spicy and savoury with some black fruit delicately shadowing red berries; fine tannins, mineral length and energy.

Pedro Parra Trane Itata Valley Cinsault 2018

One of a trio of single-vineyard wines from Guarilihue, each named after jazz musicians; this one after John Coltrane. Vines almost 70 years old on shallow granitic soils with silt and stones. 30% whole bunch. Natural yeast fermentation in concrete tanks. Mostly aged in untoasted old foudres, but some in concrete. 13.5%

Succulent red fruit and spice; silkiness but also tension; sustained herbal, salty, mineral finish.

Pedro Parra Hub Itata Valley Cinsault 2018

Named after Freddie Hubbard. Vines aged almost 80 years from poor granitic soils containing a lot of iron. Only the best batches used for this wine; 40% whole bunch and each plot vinified separately. 12 months' ageing in concrete. 13%

Pinot Noir-like in its mouthwatering purity; perfumed raspberry and black cherry fruit; effortless, fine tannins; characteristic mineral vibrancy.

Pedro Parra Monk Itata Valley Cinsault 2018

Named after Thelonious Monk. Vines more than 70 years old in Guarilihue on deeper granitic soils with clay. 30% whole bunch. 12 months' ageing in untoasted old oak foudres. 13.5%

Firmer and more structured than both Trane and Hub; mineral, savoury and still tightly wound (at the time of tasting) but full of interest; has time on its side.

Clos des Fous Locura 1 Alto Cachapoal Chardonnay 2016

From two cold, high-altitude vineyards in the Andes, one on sandy clay full of volcanic rocks and the other alluvial with gravel and limestone. Fermented with wild yeasts in stainless steel and aged on lees for 12 months, five percent in used oak barrels. No malolactic. 13.5%

Tasted two weeks ago: mouthwatering smoky-mineral aromas; ripe, crisply defined lemon fruit, rich texture, a suggestion of cashew nut, saline intensity; long and very fine.

Clos des Fous Pucalán Arenaria Aconcagua Costa Pinot Noir 2016

Clones from Burgundy, including Vosne-Romanée and Gevrey Chambertin on four hectares planted at very high density eight km from the Pacific Ocean. Low-fertility paleozoic sandy limestone with a clay surface surface giving yields of just 400g per vine (25hl/ha). Slow fermentation in large cement vats, then aged for 18 months in new Vosges-oak barrels prepared at the winery. 13.8%

Fabulous raspberry and cherry Pinot Noir perfume, exceptional silkiness, fine tannins and salty persistence.

Clos des Fous Pour Ma Gueule Itata Valley 2017

Cinsault with 9% País and 4% Syrah, from soils containing some quartz. Each variety vinified and aged separately. Fermentation in concrete and stainless steel tanks, then malolactic in tank and old barrels. Blending after 12 months. 14%

Smoky, peppery, sweet wild-berry fruit; rounded and appetisingly fresh.

Clos des Fous Cauquenina Itata Valley 2016

30% País, 25% Carignan, 22% Syrah, 15% Malbec (from Bío Bío) and 8% Carmenère from ancient red granite slopes. Slow fermentation in cement vats, each lot vinified and aged separately. 15–20% aged in new French oak barrels, the rest in one-year-old barrels. 14%

Savoury earth and salty, mineral freshness flowing through ample, fleshy fruit and smooth, discreet tannins.

Clos des Fous Tocao 2014

From a Malbec vineyard planted in 1914 on granite in San Rosendo, southern Bío Bío. Fermentation in concrete vats, then almost two years in Allier oak, 30% of it new. 14%

Dark, powerful, rich wine packed with dense, ripe black fruit and ripe tannins; redeeming bright finish, but perhaps could have been picked slightly earlier.

Clos des Fous Grillos Cantores Alto Cachapoal Cabernet Sauvignon 2014

From a vineyard at the foot of the Andes with alluvial deposits, limestone and granite gravel and steep diurnal temperature differences. Four-week vinification, including 5–7-day cold maceration and a post-fermentation maceration, then 18 months' ageing in a combination of wood and cement. 14%

Intense and insistent with plush black-cherry fruit, savoury, peppery spice, rounded tannins and a green-herb lift. The 2015, which I also tasted the 2015, has even more minerality and elegance.

Importer: Liberty Wines, London

Retail stockists (note that some are earlier vintages than those tasted above)

Clos des Fous Locura 1 Alto Cachapoal Chardonnay 2016, £17.50–£17.99 Waitrose Cellar, Champion Wines Ltd, The Fine Wine Company

Clos des Fous Arenaria Aconcagua Costa Pinot Noir 2014, £37.99 AG Wines, Quality Wines, Wells www.qwines.co.uk

Clos des Fous Pour Ma Gueule Itata Valley 2017, £15.99

Latitude Wine Ltd, Simply Wines Direct, Quality Wines, Wells www.qwines.co.uk

Clos des Fous Cauquenina Itata Valley 2016, £17.99

Selfridges, Philglas & Swiggot, Noel Young Wines, Tivoli Wines, Quality Wines, Wells www.qwines.co.uk

Clos des Fous Grillos Cantores Cabernet Sauvignon 2014, £16.99 The Fine Wine Company, Champion Wines Ltd, The Wine Reserve, Nysa Wine & Spirits, The Whisky Exchange, Quality Wines, Wells www.qwines.co.uk Pedro Parra Imaginador Itata Valley Cinsault 2017, £17.99 The Fine Wine Company, Quality Wines, Wells www.qwines.co.uk Pedro Parra Pencopolitano Itata Valley Cinsault/Pais 2017, £17.99 The Fine Wine Company, The Butlers Wine Cellar Ltd, Quality Wines, Wells www.qwines.co.uk

Pedro Parra Trane Itata Valley Cinsault 2018, £29.99

The Fine Wine Company, Quality Wines, Wells www.qwines.co.uk

Pedro Parra Hub Itata Valley Cinsault 2018, £29.99

The Fine Wine Company Quality Wines, Wells www.qwines.co.uk

Pedro Parra Monk Itata Valley Cinsault 2018, £29.99

The Fine Wine Company, Champion Wines Ltd, Quality Wines, Wells www.qwines.co.uk

Photographs by Joanna Simon

Commentaires